Introduction

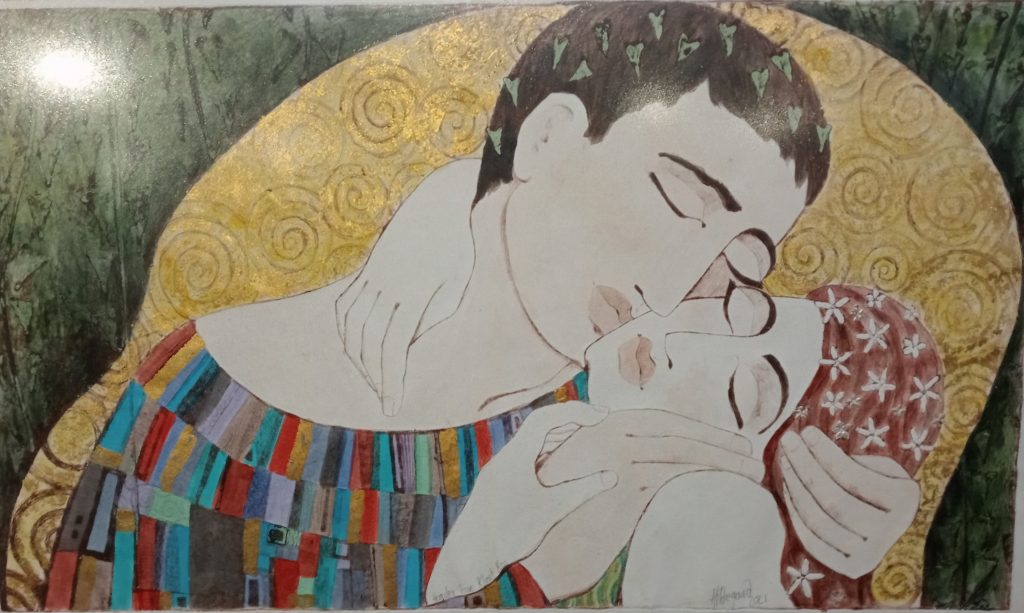

Infant mental and emotional health for midwives and health professionals is a vast subject. Medical and health professionals need to be able to support interactions between the baby and her parents and be able to recognise early attachment difficulties. Infant mental and emotional health refers to the capacity of the baby to bond and attach to a safe parent figure. Responsive early relationships provide the matrix for all learning and growth, for all future thinking skills, social relations and emotional development of the infant. Not only is the birth important for the mother and baby, but what happens to the dyad in the first six weeks, the first three moths, six months and first year of life is crucial for the emotional wellbeing of the infant.

While a parent forms bonds towards and with her baby, the key word ‘attachment’ signifies the relationship of the baby to the mother/caregiver/ parent. Attachment is a biologically driven need of the infant to seek safety in proximity to an adult figure. How the mother/parent feels towards their baby, the way in which they they hold their baby, touch the baby, speak to the baby, clean the baby all matters deeply. It is in all the daily care giving that responses are created

Infant Mental Health in the First Three Months

A strong attachment to a primary figure is the basis for all future learning. This includes emotional and cognitive/mental development. In other words, the baby needs to be in close proximity to a caregiver, not only for survival, but also for the development of language, of thinking and of relational skills. The three months after birth is an intense period for attachment and growth.

During the first three months after birth, the baby has an intense need to be close to one or two caregivers, and to be demanding of the mother/caregiver for food, warmth, responsiveness and comfort. Some babies are more fussy and cry more than others draining the mothers/parents personal and emotional resources

The intensity of the baby’s need or fussiness can trigger the mother or caregiver’s own unrecognised trauma, and lead to difficulties in the relationship between mother/caregiver and baby. A depressed parent responds to her baby less. Facial expressions are muted. The parent may not talk or light up when she holds her baby. The parent may cry or complain and not play with her baby. This can lead to a baby that appears passive.

Parental Trauma

Was the mother(or father) herself a wanted baby, does he/she have embedded trauma with regard to how he/she herself was handled as a baby? What is the relationship the pregnant person has with their own mother or father? Childhood trauma in a pregnant person may not only affect the way they will give birth. Childhood trauma may also affect a parents capacity to be confident in caring for their own infant. Furthermore, babies need ongoing care and this can be exhausting for the parents.

Equally, when a mother is unable to be warmly responsive towards her baby, the baby may exhibit symptoms of distress such as irritability, constant crying, inability to settle, or disengage from eye contact. Additionally, when a father is unable to engage warmly with his babies and children, this is a loss of opportunity for the baby to relate.

When the early relationships between mother and baby are fraught with tension or lack of responsiveness, this can negatively affect the emotional and mental health of the baby.

Types of Attachment

The way a baby and infant develops depends heavily on how the attachment figure (Mother/caregiver) relates to her baby. It essentially requires a mother to be content and confident within herself, so that the baby, toddler and child can rely on the parent for consistent responsivity. In this way an infant can feel secure and safe, and subsequently use his energy to grow and explore his world. Information is absorbed through each developmental stage of growth during infancy and childhood.

Attachment research focuses on the quality and the nature of the mother/ caregiver’s sensitivity and responsivity to her infant. There are four generally accepted main styles of Attachment to the attachment figure:

Secure Attachment

Secure attachment describes an attachment where a baby and infant feels safe and protected by the caregiver and can rely on the caregiver/parent to provide consistent safe responses. The parent is available and responds to the infants needs for interaction as they develop and change. This provides a safe environment with many opportunities for play.

Avoidant Attachment

Describes and attachment style an infant develops when the caregiver does not show care and responsiveness beyond providing essentials like food, cleanliness and shelter. For instance, the caregiver avoids eye contact with the baby. Or the caregiver handles the baby roughly, or leaves the baby for long hours in a cot or room without human interaction.

Ambivalent Attachment

Is characterised by a child’s feelings of anxiety and preoccupation as to whether the caregiver/parent is available. In other words, the caregivers responses are inconsistent, sometimes available and at other times absent, or unavailable. This type of parent may be warm and attentive at times and at other times angry and hostile. The baby is unable to anticipate the possible response of the parent and may become hypervigilant or irritable.

Disorganised Attachment

When the parents/caregivers show inconsistent responses and display erratic behaviour towards the baby or infant, the baby becomes fearful, chaotic and hyper-vigilant, and has difficulty forming close relationships with others. This style often presents when infants experience physical, emotional or sexual abuse from their caregiver’s/ parents.

How can Parents Prepare ?

The biggest task for parents/caregivers is to become self-reflective and manage their own feelings and triggers so they are not reactive towards their babies and infants. How does this translate into real life? It means that parents need a support system so they have other adults to talk to and share their difficulties with.

It means that all the thousand acts of kindness in caring for a baby such as feeding or changing a nappy are performed consistently and steadily while engaging with the baby/infant in warm responsive ways. Taking care of the parent’s own needs and reaching out to others when feeling overwhelmed is essential.

In more serious cases of parental depression, therapy and guidance may be crucial.

- Discovering family constellations and family ancestral relationships can be useful

- Understanding own style of attachment to one’s own parents is important.

- The parent’s own feelings of anxiety, attachment, loss, grief, anger or numbness will have an effect on how the baby/infant is able to relate and attach to the caregiver/parent.

- Seek counselling during the pregnancy when overwhelmed

- ‘Look Back’ to uncover trauma, so as to clear the way ahead for one’s own parenting journey.

- Good antenatal care with a listening midwife or doctor help to alleviate anxiety during pregnancy and follow up on specific difficulties

- Bonding with the unborn baby during pregnancy can be facilitated by counsellors specialising in perinatal psychology

- SEEK help when life becomes overwhelming and find support systems, counsellors, and networks of other mothers, family and friends who are supportive.

- Antenatal Classes can help to allay anxiety about the birth and improve one’s coping skills.

- Aware Parenting (http://www.awareparenting.com) is a set of tools and skills parents can learn through a mentor

How can Midwives and Health Professionals Assist?

Midwives and health professionals will do well to reflect on their own personal trauma and how their own story impacts on the work they do with mothers and caregivers in the early parenting year.

Long hours and large caseloads of clients can be exhausting for midwives and health professionals. Burnout is common among midwives and other health professionals.

Midwives work under huge stress, often making life and death decisions with their clients and need a platform where that can share their personal experiences without fear of judgement. Health professionals and midwives need to unburden from the emotional and psychic stress of working in a high performance environment.

Health professionals and midwives are more effective when they have sufficient time to rest and recoup, are fulfilled and well supported by counsellors, peers, and close friends and family.

Tools

The Edinburgh Post Natal Depression Scale is a useful tool for midwives to assess which mothers/parents may be suffering from undue anxiety during pregnancy. Maternal Mental Health services are a great resource for mothers / parents and midwives, such as the Perinatal Metal Health Project in South Africa.

Tips for supporting responsive parenting:

- Ask leading questions and for more information

- Listen, don’t judge, and try not to give advice

- Give parents a chance to talk

- Initiate and encourage breastfeeding and infant feeding

- Encourage postnatal support groups, well baby clinics and social gatherings

- Encourage skin to skin contact post birth

- Prepare parents for birth and early parenting

- Be aware that depression during pregnancy can affect the pattern of fetal movements in the womb. Teaching pregnant parents to count the number of kicks and intra uterine movements is a way of being alerted to negative emotions as well as possible negative outcomes.

Conclusion

The Author Sue Gerhard who wrote the book ‘Why Love Matters’ in 2014 stated that “Gestation is a mutual construction process” and the mutual relationships of parenting begin in the womb. We are all involved and we are all part of the community that gestates our children for the future. It is important for all of us to contribute and make an effort to create an environment in which babies can attach securely to their caregivers/parents.

References:

- Gerhardt, S. 2014 Why Love Matters. Routledge. Psychology ISBN 9781317635796

- Mmabojalwa Mathibe-Neke J. &Masitenyane S. 2018. Psychosocial Antenatal Care: A Midwifery Context. In Selected Topics in Midwifery Care 2018 edited by Ana Polona Mivšek. DOI:10.5772/Intechopen 80394