Violence in Maternity care is the intersection between institutional violence (of a system) and violence against women during pregnancy, during the actual birth and during the post natal period after the birth.

Obstetric violence occurs through both invasive practices like performing an examination without a woman’s permission as well as through the denial of treatment during childbirth. A woman may be ignored and left unattended during labour, denied pain relief, and/or verbally humiliated. Assistance to a woman transferred from one facility to another may be delayed unnecessarily. A woman in labour may be slapped, hit, forced to lie in an uncomfortable position, and be coerced into receiving unnecessary and or unwanted interventions or medication. Women in some countries are discharged from hospital and their babies are detained in hospital until the mother pays the bill. Pregnant women are often discriminated against for their race, ethic group, their age (e.g.teenage girls), their HIV status or gender non-conformity (eg. a lesbian or gay couple). Obstetric violence is often overlooked and normalized and is a form of violence against pregnant women and both unborn and newborn babies.

I once assisted a sex-worker, whom I shall call Maria, to give birth at a Birth Centre in Cape Town. At that time we undertook to help all pregnant women from a local Home for unmarried mothers voluntarily (i.e. for free). Maria had decided this baby would be given up for adoption. I took her into the birthing room and she stepped carefully and slowly across the threshold and through the door. Maria turned her head to look at the warm curtains, then looked at the inviting bed with its cream duvet and pillows. Maria turned her head again and gazed at the large bath tub. She turned to me and asked ‘Am I allowed to be here? Can I really give birth in this room?” I said yes, you are in labour and you deserve to be comfortable. You are special. The corner of her lips turned up as a large teardrop rolled down her cheek. I opened the tap to run a bath, full of warm water, and offered to help her get in to the tub. Maria laboured without complaint. I wiped her forehead, I offered water in a glass to sip, I held her hand. I encouraged her and believed she was worthy, she could do it. Time passed, a beautiful baby boy slipped into the water and I lifted him onto Maria’s chest where she clasped him with both hands. A stream of sunlight rested on mother and baby through a gap in the curtains. I stepped back, humbled, as this pair greeted each other and said their goodbye’s. Maria had been so used to being looked down upon, being abused, being mistreated that she did not believe she was worthy of humane medical and midwifery care. She was worthy, so worthy.

10 ways to say No to Violence against Women and Children in Maternity Care

1. Make Healthcare for pregnant women and women in childbirth available to every woman

It is not uncommon for doctors in the private sector to refuse to assist women who want vbacs or hbacs. Compounding that, in rural areas in Africa there are just not enough doctors, midwives or healthcare facilities.

2. Treat each woman with respect and dignity: Address her by name, provide privacy, speak in a respectful tone

and language

For example, doctors and midwives use terms such as ‘Mummy’ and ‘lady’ or say harsh words such as “You did this to yourself, now push harder”, or similar. Privacy is often an issue, with curtains around beds being left open, exposing patients unnecessarily, or not covering patients adequately.

3. Provide the relevant information and education for her obstetric needs

Each mother deserves to know what labour is and how it naturally progresses. She deserves to know what her illness may be and what it means for her and her baby.

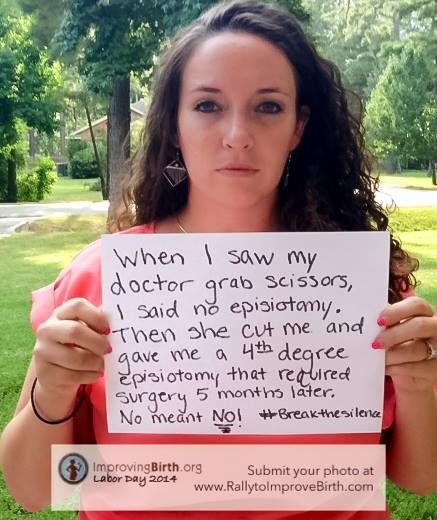

4. Ask permission, obtain informed consent and explain consequences before any medical intervention

Midwives and doctors need to explain all risks and benefits in as objective a way as possible, and not coerce or force women to accept interventions such as an unwanted and unnecessary episiotomy or an unnecessary caesarian section.

5. Make it mandatory in all birthing facilities that a birth companion is present for each woman

It is still true that many hospitals will not allow a birth companion/doula other than the husband remain with a mother when she is in labour. Allowing ‘Doulas’ is a proven way of reducing caesarian sections and improves outcomes.

6. Train Health Care Workers in respectful maternity care

Training and practice for staff in compassionate maternity care includes teaching about Human Rights in Childbirth, how to obtain informed consent, how to provide physical and emotional support to women in labour (such as massage), as well as the idea of “offering rather than asking”.

7. Offer counselling services to women affected by trauma as well as to health care workers

Debriefing and counselling for staff when births are traumatic is very important to their continued development. Counselling and follow up for women who have experienced traumatic births – even more so.

8. Support the Basic Needs of a Woman in Labour

Namely, be kind, turn down the lights, give her privacy, keep her warm, respect her need to move about and her right to give birth in a position of her choice – i.e. other than lying on her back.

9. Support a woman’s choices for her birth, even when those choices are deemed to be going against medical advice

Support women who have had multiple caesarians when they ask for a trial of labour: in many cases denial of these services pushes women underground when they have a right to attempt a vaginal birth after caesarian (VBAC).

10. Talk to each other

When midwives and doctors, psychologists and natural health practitioners work together and share information about their mutual clients, the client benefits, transfer of clients from home to hospital is safer when doctors and midwives communicate and work together.

Small steps by each birth professional can make a big difference to all women when they are pregnant and giving birth. Rachel Chadwick states in her guest editorial for the South African Journal of Medicine: “The medical establishment needs to recognise forms of abuse during labour and childbirth as more than the actions of a few misinformed individuals and to address wider systemic sexism and classism in medical training, established protocols and attitudes towards childbearing women and girls”.

When women feel heard and welcomed by hospitals, birth centres, doulas, doctors and midwives, their babies are likely to feel welcome too. And each baby carries the future of our world in their hearts. We need to take care.